Most competent programmers are aware that linked lists are inefficient data structures, simply because they do things which modern hardware struggles with. Having indiviual elements point out to the next element (if any) is much less efficient than simply grouping elements next to each other in memory and prefixing them with the number of elements. The opening paragraph of the wikipedia article on linked lists points this out. The documentation for linked lists in the Rust standard library points it out in CAPS.

Here is a hot take: LEB128 — the most widely-used variable length integer encoding — is the linked list of varints. The basic idea is to represent an integer as a sequence of bytes. The first seven bits of each byte encode information about the integer, and the final bit indicates whether the end of the encoding has been reached or not.

For computers, this format is a pain to decode. Modern hardware wants to operate on multiple bytes simultaneously whenever possible (even without SIMD, processing still happens at words of multiple bytes), but an LEB int must be processed byte by byte. And for every single byte there is a branch which is highly difficult to predict.

Analogous to data structures for sequences, a much better design is to provide the length up front and to then have the actual data in a contiguous chunk. CBOR got this right, I humbly offer the VarU64 spec and the way we encode integers in Willow (which is essentially a generalisation of the CBOR design), other people have proposed similar designs. The exact choice between any of these barely matters. But they are all significantly more efficient than LEB128. And as a bonus feature, comparing their encodings lexicographically coincides with numerically comparing the encoded integers, which can be helpful when working with kv-stores — but is not the case with LEB128.

For the most part, this does not really matter. Very few systems will critically suffer from the performance penalty implied by LEB128. I just find it curious that so many competent engineers simply accept the very first design they stumble upon. And where is the warning in the first paragraph of the Wikipedia page on LEB128? Why does that page only provide links to “related encodings” that replicate the same design choice, instead of discussing alternatives?

Oops, looks like this week turned into a week of rants for me. Oh well, going forward I will at least be able to link to these pieces instead of repeating the same rants over and over in different discussions.

~Aljoscha

Kids these days. Keep on yapping about CRDTs, as if they found the best thing since sliced bread. Even though everyone knows the best thing since sliced bread is actually blockchain the internet of things artificial intelligence service-oriented architecture!

To recapitulate, an operation is called commutative if the order of its arguments does not influence the result. Quite obviously, if you only use commutative operations, then the order of your inputs does not matter. What else is new? Sure, “operation-based CRDT” sounds moderately impressive, but all you are doing is to apply a commutative (and associative) binary operator.

Technically, when you also add idempotence, you get a semilattice (operation-based CRDTs and state-based CRDTS are technically equivalent, after all). But let’s face it, most operation-based CRDTs in the wild are ad-hoc commutative operators that do not derive value from any underlying algebraic structure.

Did you know that you can turn any non-commutative operator into a commutative version by consistently permuting its arguments? For example, while subtraction is not commutative, an operator that takes two numbers and always subtracts the smaller number from the larger one is commutative. You can also make any operation idempotent if you require the arguments to carry a unique id, and keep track which ids you already processed.

So when a data structure expects all operations to arrive in sequence and has to store them all forever, so that they can be deduplicated and sorted, so that they can be made idempotent and commutative, so that the whole thing becomes an operation-based CRDT, forgive me if I am not particularly impressed.

Now, state-based CRDTS, on the other hand — or semi-lattices as they have been called for decades prior — are great. They provide sufficient algebraic structure to be actually useful, allowing for universally-applicable optimisations such as delta CRDTs (that paper also provides a definition of the concept of irredundant join decompositions, which is central to most interesting CRDT questions). Here are a couple more ideas of what could be explored:

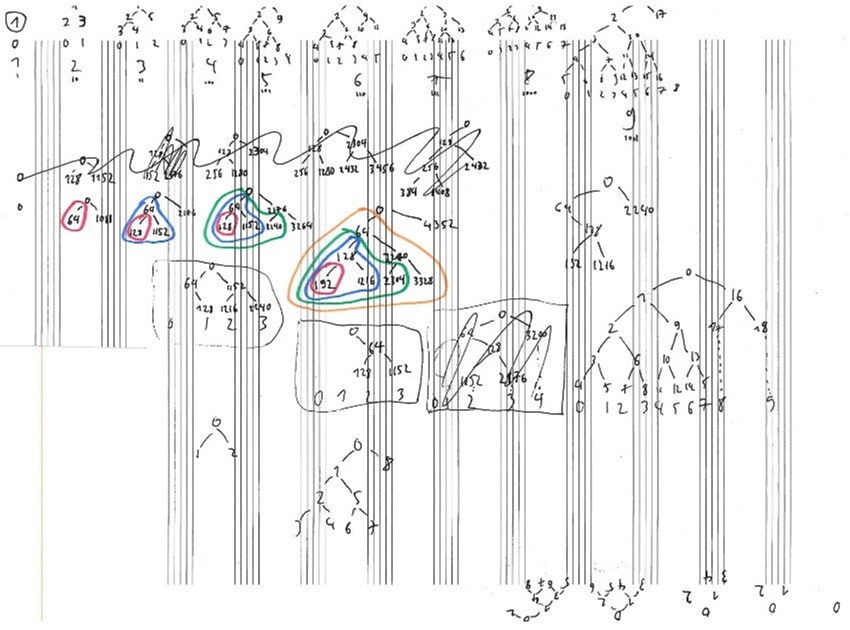

If your application state is a join-semilattice, then you can represent it by building a tree whose leaves are the elements of the irredundant join decomposition of your state, and whose internal nodes store both the join over all children of the subtree and a hash of that join. You could use that tree to power a tree-based set-reconciliation algorithm (whether based on history-independent trees or not), giving you logarithmic-time state updates and the ability to synchronise them efficiently. More generally speaking, generalising set-reconciliation to join-decomposition-reconciliation seems quite promising (see, e.g., arxiv.org/pdf/2505.01144).

How do irredundant join decompositions relate to information-theoretic bounds on synchronisation traffic in general, and to compression of CRDT updates in particular? Lattices admit a clean representation theory (see Davey and Priestley chapters five and eleven) in terms of irredundant decompositions. Thus, it should be possible to define encodings purely in terms of these abstract representations, which could ideally lead to provably optimal encodings of updates irrespective of the details of the particular lattice.

The CALM theorem states that conflict-free updates must monotonically progress in some partial order. This does not mean, however, that the amount of information you need to track has to increase monotonically as well. Willow provides an example, where a single newer (i.e., greater-in-the-CALM-relevant-order) entry can overwrite many older entries, thus deleting information. What does this look like from a more general lattice-theoretic perspective? When some join-irredundant element is in the irredundant join decomposition of some state, then no other element less than it can be part of that decomposition. In other words, join-irredundant elements “high up” in the partial order of the lattice enable deletion. Can we design for the existence of such join-irredundant elements? Which algebraic properties hold in lattices where we have upper bounds on the length of maximal chains which do not involve join-irredundant elements? Can we leverage such upper bounds for efficient encodings of updates? Do bounds on the largest anti-chains factor into this as well? What are good formalisms to quantify the “deleted information” of join-irredundant elements (a good starting point might be to define a a non-lossy lattice which carries around all elements which have been join-irredundant at any point; there should be a natural lattice-homomorphism from any lattice into its non-lossy counterpart that would serve to compare the two at any point in the original order)?

In a network where multiple peers synchronise state via a CRDT, which optimisations can we enable if we get to assume that peers cannot lag too far behind? How do we properly define that in the first place — maximum distance between greatest and least state when interpreting the partial order as a directed graph? And once we have a suitable notion of such bounds, how can we automatically determine which information we can now drop? In other words: whereas join-irredundant decompositions are defined in terms of the full lattice, which meaningful (and practically useful) notions of decompositions can we enable by strategically cutting off elements from the bottom of the lattice (here, it can be really useful to work with semi-lattices instead of proper lattices, because in a join-semilattice you can remove minimal elements without jeopardising the semi-lattice axioms)? The braid folks have been exploring similar thoughts in their antimatter algorithm (and in general, they have been doing some nice abstract CRDT work, see, for example, their time-machine theory for unifying Operational Transformation and CRDTs).

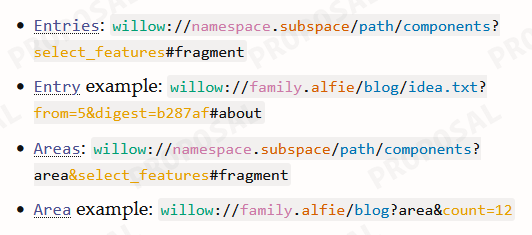

How come barely anyone is talking about sublattices? A lattice within a lattice is exactly what you need in order to support fine-grained access control while still keeping things synchronisable. Same for setups where peers are not interest in all the data ever but merely in a subset of the data. If that subset forms a sublattice, then you know that you can synchronise that data with confidence. It is no coincidence that access control and partial sync work out really neatly in Willow: every Willow Area induces a sublattice. Since, arbitrary lattices can have exponentially many sublattices, formalisms that assume that arbitrary sublattices can be expressed are probably inapplicable in practice. But when restricting the set of sublattices that can be expressed (like Willow restricts access control to the granularity of Areas), what makes for a good set of sublattices? You probably want some closure properties, maybe something filter-like? I don’t know, I’m not even a mathematician, I just want more people to ask these questions! Because it feels scary to merely intuit that Areas are a good choice for Willow without knowing why.

Can we formalise a notion of intent-preserving lattices? When a text CRDT merges two overlapping edits in a deterministic but possibly unintuitive way, the intent of the author of either edit might be violated (and possibly even the intent of both authors). Is there a formal concept behind this human-centric notion? Staying with this example, instead of doing an arbitrary resolution, the join of the two edits could instead be a state which preserves both edits (“intents”?), at the cost of not mapping to a unique string of text. As long as such states can still be merged (accumulating ever more conflicting intents), you still have a CRDT, after all. That is basically what the Pijul vcs does. Again, can we formalise what it means that such a system preserves intents? Perhaps the existence of certain homomorphisms into the non-lossy lattice version sketched a few paragraphs earlier might be meaningful here?

All of these thoughts are merely starting points and semi-low-hanging fruits, but all of them have the potential to bring about actual engineering benefits for distributed systems. So I am all for CRDTs. But it feels to me like an increasing fraction of the usage of the CRDT terminology refers to ad-hoc variations of the brute-force approach of making arbitrary operations commute by applying updates in a consistent order (i.e., by sorting their arguments). Of course it is nice if a bunch of local-first applications speed up because somebody made a“JSON-CRDT” 10% faster. But that is not how we will make any qualitative progress on the road to ubiquitous peer-to-peer software. As uncomfortable as it may be, that will require actual math, not just repeating “CRDT” often enough to turn it into a buzzword.

Many thanks again to

Many thanks again to  And thank you to

And thank you to

Firstly, we’ve reworked

Firstly, we’ve reworked

For breakfast I often turn to the humble porridge. I like to put big chunks of apple in my porridge which cook just long enough to get soft but still keep their structure, kind of like in an apple pie. I like to cook my porridge low and slow, which really annoys everyone else.

For breakfast I often turn to the humble porridge. I like to put big chunks of apple in my porridge which cook just long enough to get soft but still keep their structure, kind of like in an apple pie. I like to cook my porridge low and slow, which really annoys everyone else. You can't go far wrong with a curry. I break up a cauliflower into little florets and roast them in the oven until they start to caramelise at the edges. I could eat them just like that, but in a curry sauce they're even better. I make a curry sauce from scratch and it is completely inauthentic.

You can't go far wrong with a curry. I break up a cauliflower into little florets and roast them in the oven until they start to caramelise at the edges. I could eat them just like that, but in a curry sauce they're even better. I make a curry sauce from scratch and it is completely inauthentic. Salmon is great when you're low on time because you just smack it in the oven for a bit. In the colder months I like to do a roast vegetable mix alongside it: potato, beetroot, sweet potato, red onion, topped with some capers. The purple of the beetroot and onions look so good next to everything else.

Salmon is great when you're low on time because you just smack it in the oven for a bit. In the colder months I like to do a roast vegetable mix alongside it: potato, beetroot, sweet potato, red onion, topped with some capers. The purple of the beetroot and onions look so good next to everything else. And when it all became too much for me I just ordered pizza. hashtag winning

And when it all became too much for me I just ordered pizza. hashtag winning