“is there a homomorphism from your opinions to our opinions?”

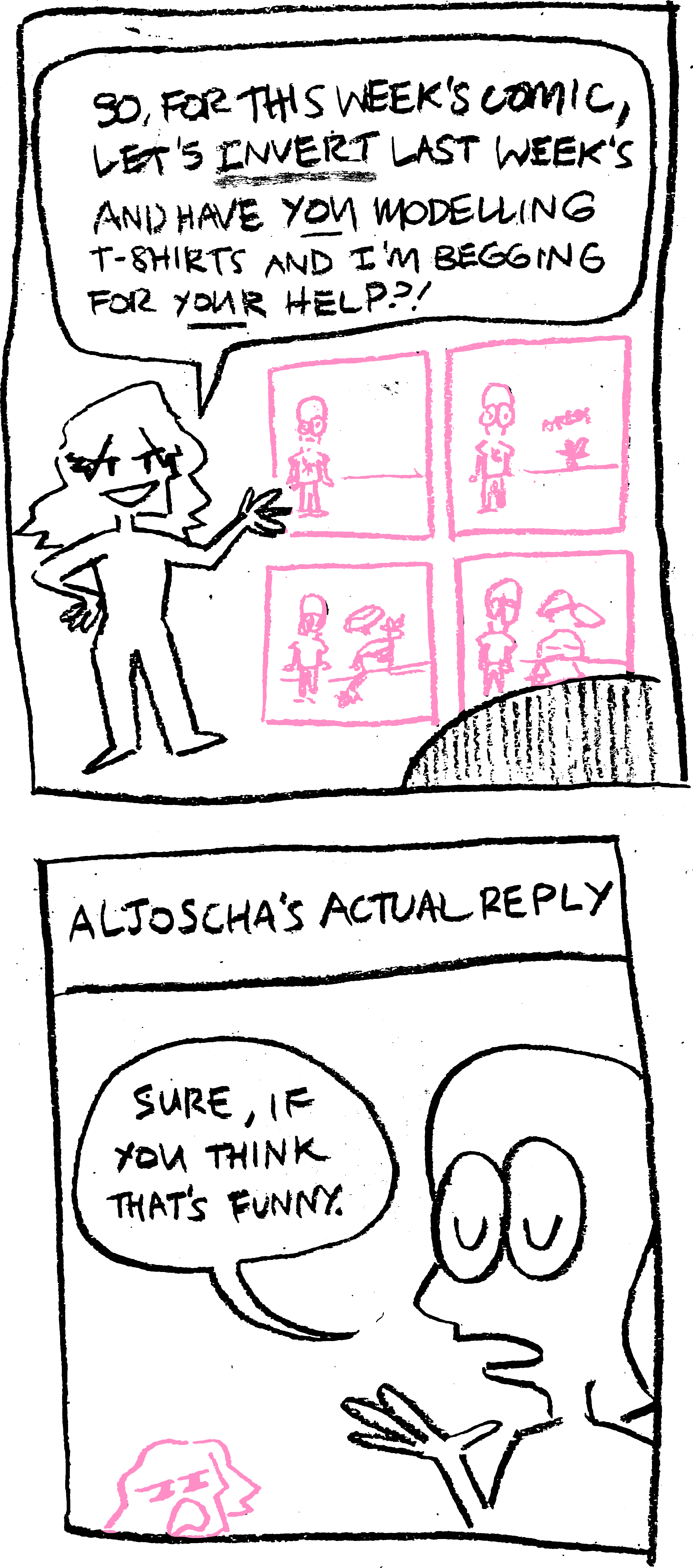

Let’s start with nuts and bolts dev diary stuff: I started working on a new persistent store for Willow. It’s a straightforward port of the previous persistent store, which used sled under the hood. Except things were just different enough that I could justify switching to Fjallinstead. Translating from sled’s APIs to fjall’s was pretty straightforward! This store is missing a few pieces still, as the Store trait needs to be updated with a few methods for storing and retrieving payloads, which depends on the Bab work Aljoscha has been feverishly boshing away at. So: we’re getting there!

While that bubbles away, what else to do but learn about Tauri, and seeing what I can glue together with our Willow Rust APIs? I got about as far as creating one button before my head filled with question about how we’re going to present all of this to human beings. Like the keypairs which are used to sign entries, for instance. they’re just not anything like user accounts on something like Discord, or even Mastodon.

Since the earthstar days, we’ve referred to the set of features keypairs confer as an ‘identity’. But to me, identity smacks of some kind of vague proving humanity rubbish. But that’s kind of exactly the opposite of what we want Willow’s keypairs to do:

- they can be used to prove authorship

- but you can have a lot of them

- and they have as much or as little identifying information attached to them as you want.

So how about ‘persona’? Data can be verified to be written by a persona, you can have as few or as many as you like, and you can attach as much ‘identity’ information (e.g. display name, avatar) you want… or not. Miaourt suggested using little masks as the iconography for this, which I really love.

So how about ‘persona’? Data can be verified to be written by a persona, you can have as few or as many as you like, and you can attach as much ‘identity’ information (e.g. display name, avatar) you want… or not. Miaourt suggested using little masks as the iconography for this, which I really love.

I'm not the only working on Willow GUIs right now, so expect more of this!

~sammy

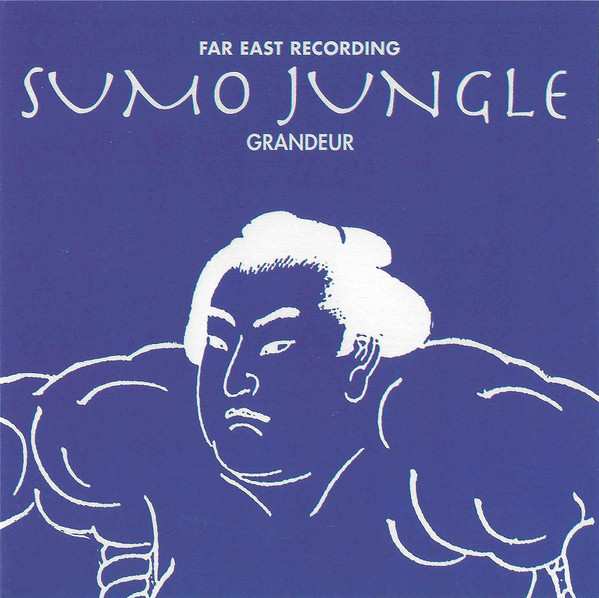

We're listening to...

Sami (yay!) shared this video on our Discord server, and I’ve listened to it several times by now. In searching for the band on the web, I found this interview with the lead singer, where they primarily talk about the band’s unconventional decision to not sell their music via larger digital platforms. The philosophy behind that is a lot more nuanced than “Spotify bad!”, I greatly enjoyed reading this. ~Aljoscha

And something completely different to Aljoscha's pick: animated mega-band Gorillaz. I remember seeing one of their animated music videos as a kid and being completely captured by Hewlett's style and the project's concept. As the years went by, it seemed that the animated aspect of Gorillaz became less and less pronounced. So last week's release of their new eight minute video was such a treat. As for the music: I have been humming the sweetly lilting flute melody from the album's initial track the whole month. And Black Thought's section in The Moon Cave imbues its animated adaptation with all its kinetic power. ~sammy

So much has happened this week! This calls for bullet points!

- Good progress on the Bab implementation: we have well-documented public API for (persistent) single-slice-per-string storage with support for partial verification. Still requires better tests, but then it can be released. Before that, I’m creating a Bab-aware trait for Willow stores in the willow25 crate though, to unblock Sammy’s implementations of a persistent store and the Willow Drop Format.

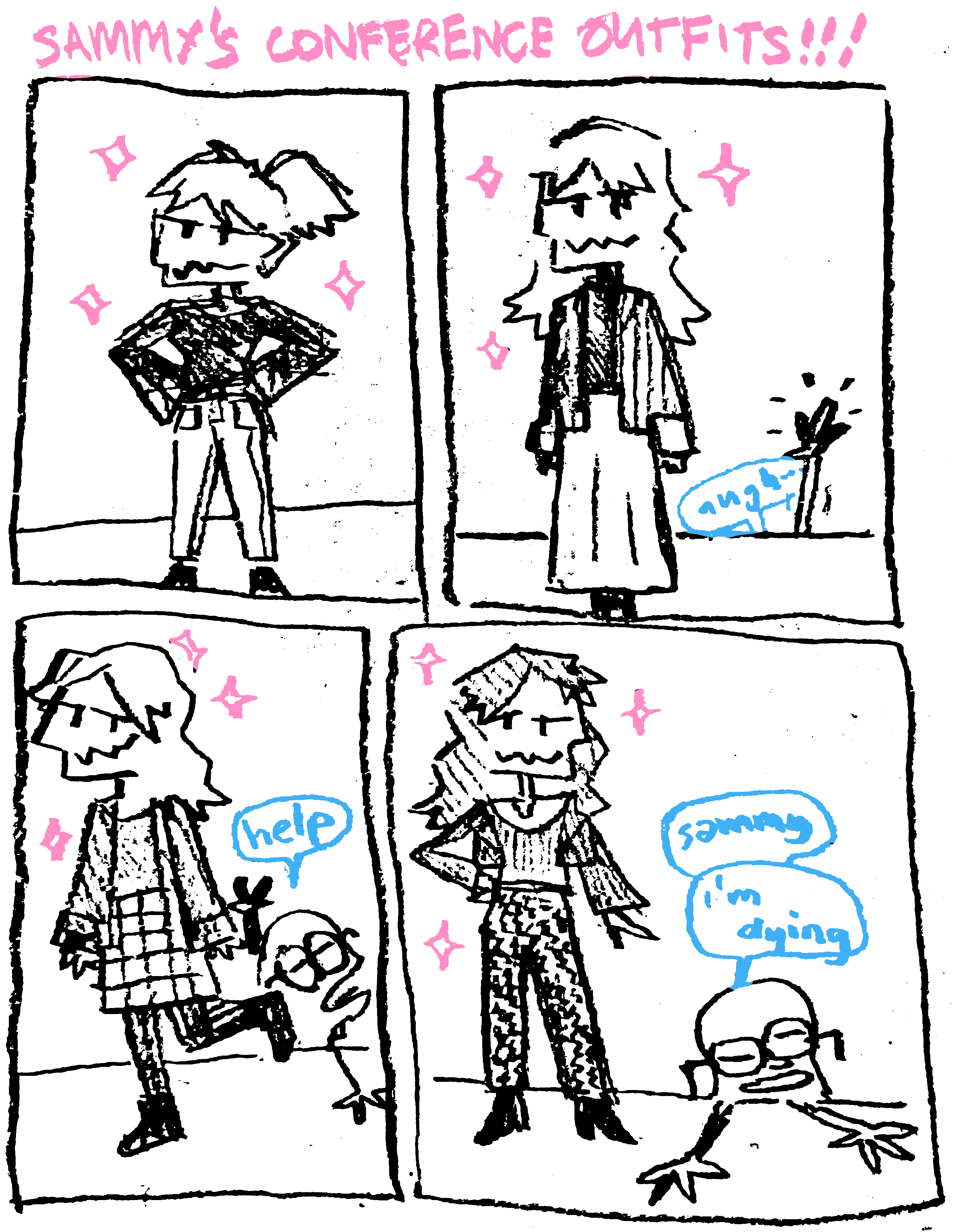

- I attended a DWeb preparation event on Saturday. Was nice to run into many familiar faces, and to get to know some new ones. Went home with renewed motivation to get Willow out into the world.

- I met with Zelf to record an episode of her podcast. It will probably be a while until editing is finished and this episode is released, though.

- On Tuesday, a bunch of us p2p nerds ended up in a bar with Olivia Jack of Hydra fame. Hydra is a super cool environment for creating 2d graphics — basically a synthesizer for graphics. I may have spent too much time playing around with it afterwards. It is so easy to get something fun going. I also may have started reading the source code and begun sketching a WebGPU-based implementation. The chances for that ever getting anywhere near useable are close to zero, but at least I had a very fun day of rest.

- I have strong opinions on variable-length integer encodings. So I was happy when I read Brooklyn Zelenka’s new bijou64 spec, which is an interesting variation on my older VARU64 specification. Slightly more complicated, but also slightly more efficient, and arguably easier to detect non-nanonic encodings. An interesting read for the other three people who care about varints.

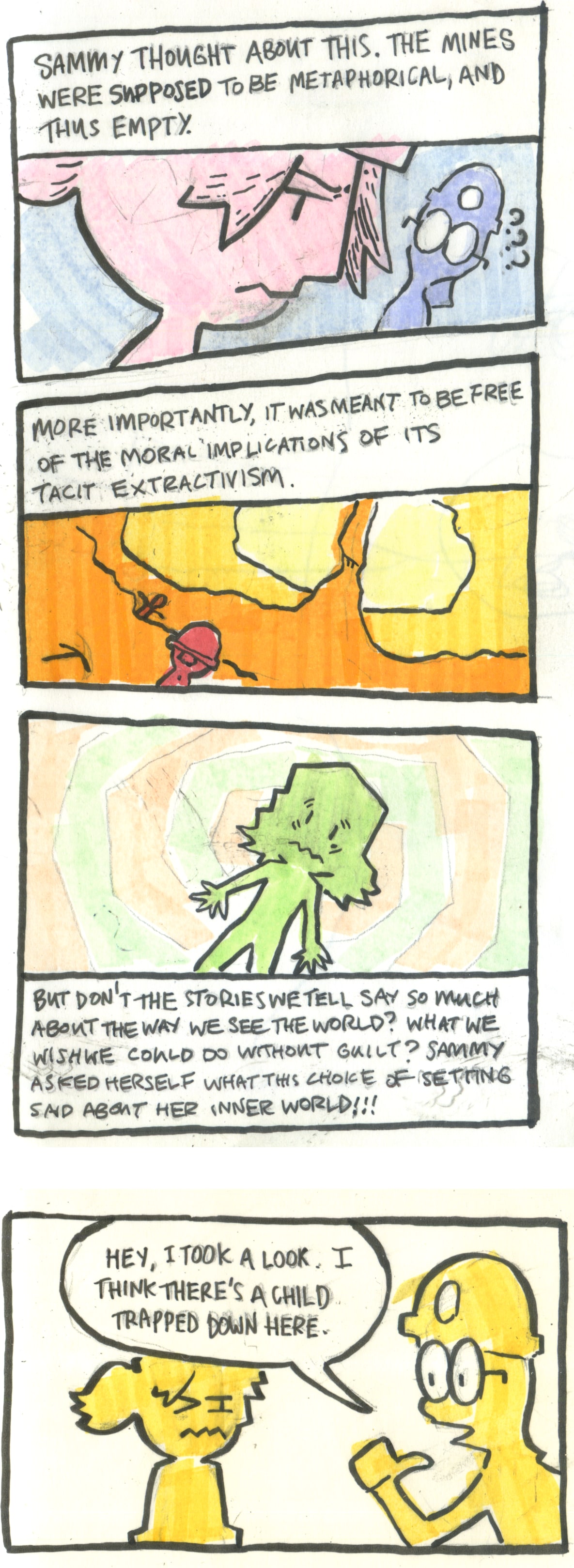

This week I finished a super secret side-project that I will reveal... later :>

This week I finished a super secret side-project that I will reveal... later :>

~Aljoscha

Shout-outs!

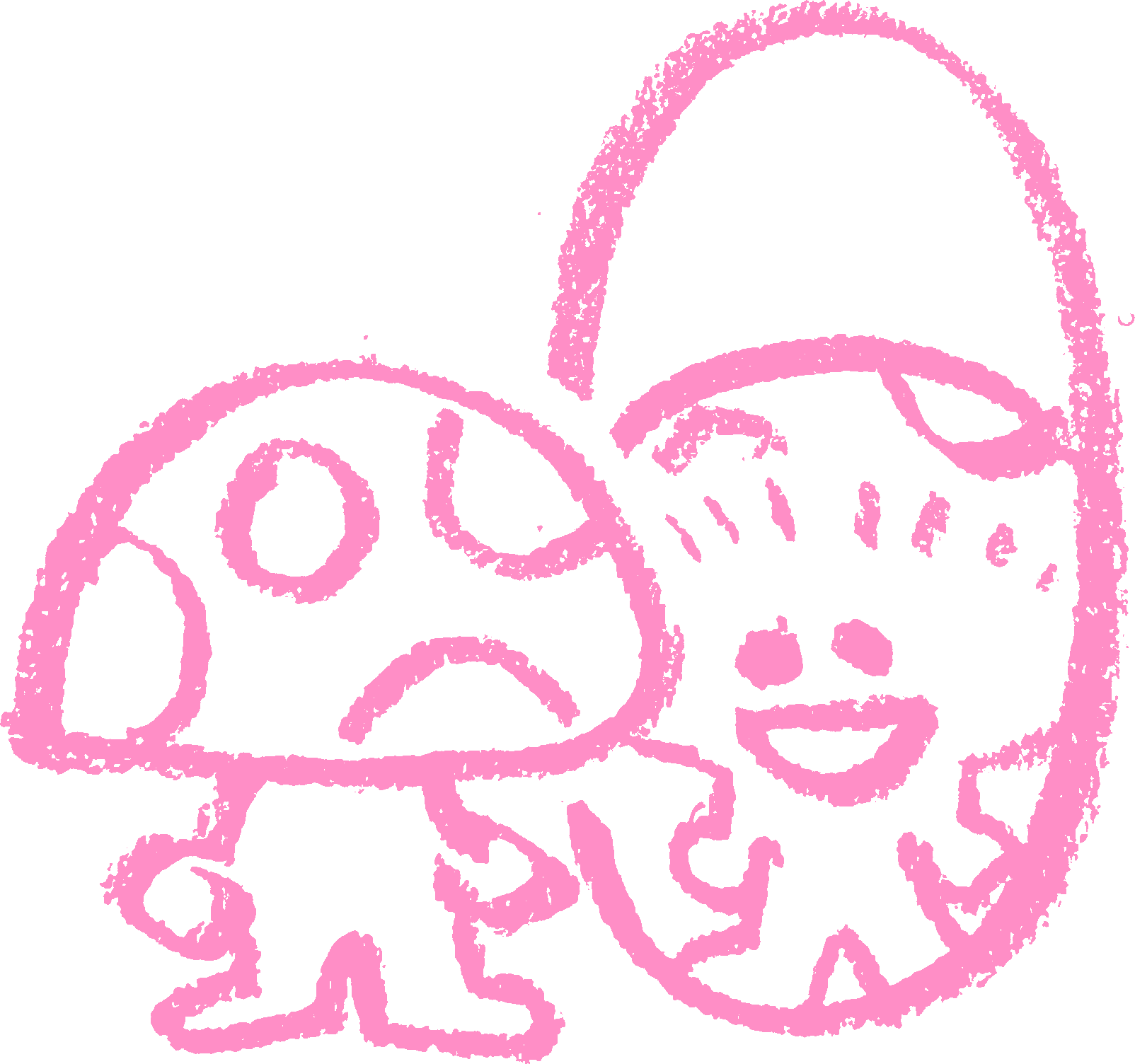

Remember the fruitful discussion about error cases of bulk processors in Ufotofu? Danmw has implemented all resulting changes. Somebody should give them a medal or something! (Sammy, you can draw a mushroom person with a medal, right?)

And the commit messages deserve a special message. Sammy and I appear to have been the worst kind of role models. Nicely wrought, Dan.

We have a new first-time contributor: 🐈⬛ added default parameters to our Rust implementation of Willow’25, allowing Sammy to progress the Willow Drop Format format a bit further. And I could finally put the signature for the default entry into the specification.

I give rather pedantic feedback on pull requests to our Rust repositories, and I’m often scared I’m overdoing it. So thank you for putting up with my nitpicking. And thank you for contributing the code in the first place, of course!

The real trouble started however once we needed willow25 wrappers for generic types made up from other generic types. For example, a generic

The real trouble started however once we needed willow25 wrappers for generic types made up from other generic types. For example, a generic

With that out the way I can get back to the important work of being a weird little frog. This weekend I’ll be heading to the Internet Archive’s new European Headquarters in Amsterdam for a little

With that out the way I can get back to the important work of being a weird little frog. This weekend I’ll be heading to the Internet Archive’s new European Headquarters in Amsterdam for a little

With no more slides to prepare, I returned to programming (shudder). It has been a while, and I feel clumsy and slow, especially in Rust. But I’ve started implementing the prerequisite encodings for

With no more slides to prepare, I returned to programming (shudder). It has been a while, and I feel clumsy and slow, especially in Rust. But I’ve started implementing the prerequisite encodings for

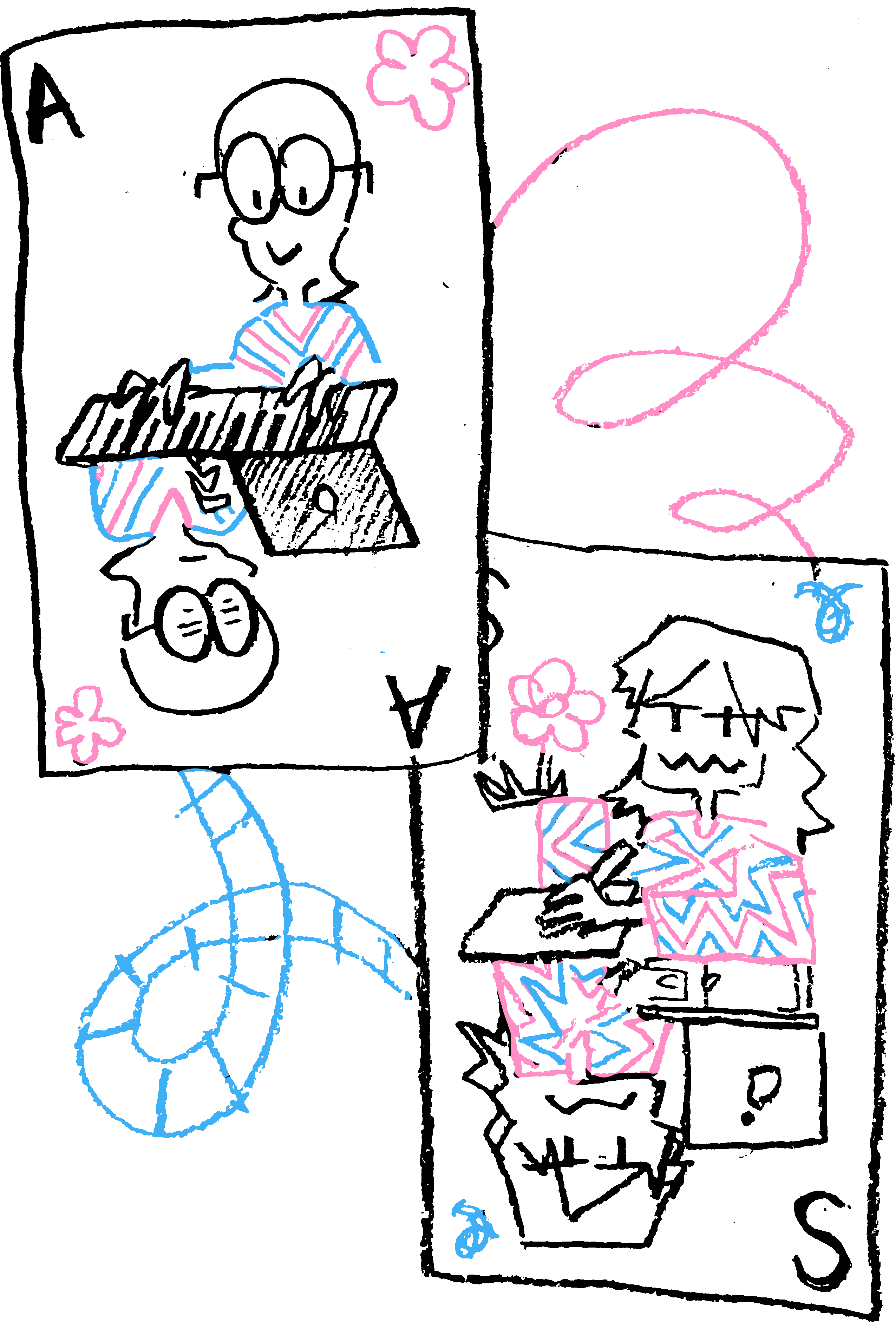

Luckily I was met by friends of worm-blossom (FoWB)

Luckily I was met by friends of worm-blossom (FoWB)