Verification in Bab

Some notes on implementing (partial, and optimised) verification for Bab. These notes assume good familiarity with the Bab spec, I am writing this for potential implementors or maintainers. And, let's face it, I'm mostly writing it for myself at this point.

Assume you already have some code that tells you for a given set of streaming parameters (e.g. “the slice starting at chunk 17, consisting of 12 chunks, using the 2-grouped light verifiable stream with a left_skip of three”) the sequence of tree nodes whose children make up the data stream, plus information on which of their child labels are omitted as an optimisation. How do you go from this information and an incoming stream of raw bytes to actually verifying whether those bytes are valid Bab data?

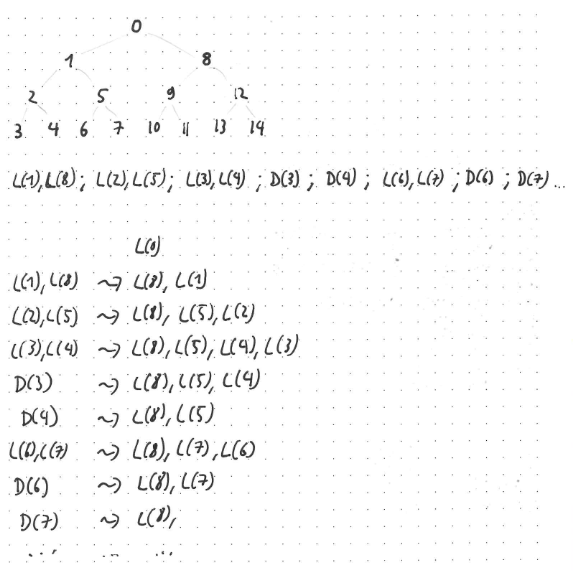

In this note, I’ll sketch a fairly elegant way of going about it. I’ll start with the simplemost case: the slice is the full string, and no optimisations are enabled, i.e., no data is skipped. Here is a drawing of a concrete example; the explanation follows the drawing:

The first part of the drawing shows the Merkle tree on eight leaves, with the nodes labelled in depth-first order. This is the order in which the nodes contribute the labels of their children to the verifiable stream. Below the tree, you see the start of the verifiable stream. It begins with the labels of nodes one and eight, followed by the labels of nodes two and five, then the labels of nodes three and four, and then the data (i.e., the raw bytes) of the first chunk (which is vertex number three), the data of the second chunk, and so on.

And below this, you see the actual verification process. The column to the left of the arrows shows which data is being read from the stream, and the right side of the arrows shows the verification state. This state is very simple: it consists of a stack of labels. Whenever you receive the next part of the stream, consisting of two inner labels, you use these two labels to reconstruct their parent label. If the reconstructed label matches the top-of-stack, things are good — if there is a mismatch, verification fails. After popping the top-of-stack and verifying equality, you then push the two received labels onto the stack (right label first, left label second).

Whenever you receive actual chunk data (as opposed to two labels), you reconstruct the corresponding leaf label, pop from the stack, and verify equality. You do not push anything onto the stack.

The initial state is the stack consisting of a single label: the label of the root vertex, i.e., the digest you have been requesting.

And that is it, maintaining a single stack suffices to verify things in the absence of any optimisations. Yay! Note that the stack is empty exactly after verifying the final chunk data, but not at any earlier point. Also note that, while I wrote down which veritices the labels belong to in the drawing, there is no need to store explicitly to which vertices the labels on the stack correspond. Storing only the labels themselves suffices, everything else works out automatically.

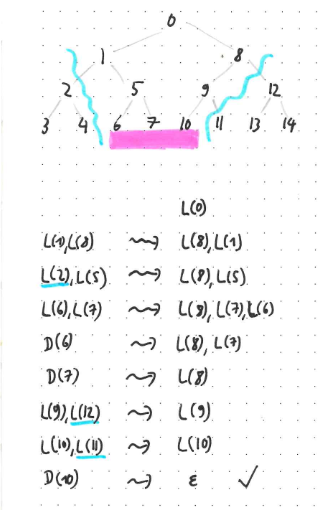

Next, we can look at a (still unoptimised) slice stream that does not cover the full input string:

In this drawing, the slice extends from chunks two to four inclusive, highlighted in pink. The blue line indicates which parts of the tree are omitted from the stream.

Verification works the same way as before, with one exception: when receiving a label whose children are omitted from the stream (those labels with a blue underline), you do not push that label onto the stack. That is it, everything else works out automatically. Yay!

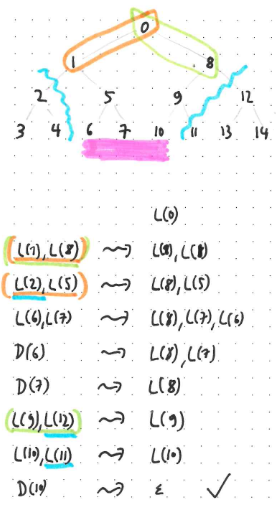

Next, let us consider left_skip and right_skip:

This example demonstrates a left_skip of two and a right_skip of two. An orange border indicates when something is skipped because of the left_skip, a green border indicates skipping because of the right_skip. Note that a single label can be skipped because of both (not that it would be super-skipped or anything).

Here is the interesting part: verification is not affected at all. The only thing you need to do differently is to retrieve skipped labels from your local database (the only sensible reason for using nonzero left_skip of right_skip is because you already have the information that will be skipped) instead of reading the labels as bytes from the incoming stream. Easy. Yay!

Sadly, the final optimisation does complicate things quite a bit. This optimisation is the fact that certain labels can be omitted from a stream, either through left-label omission or through k-grouping.

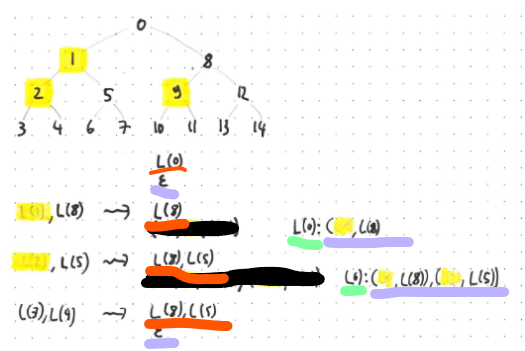

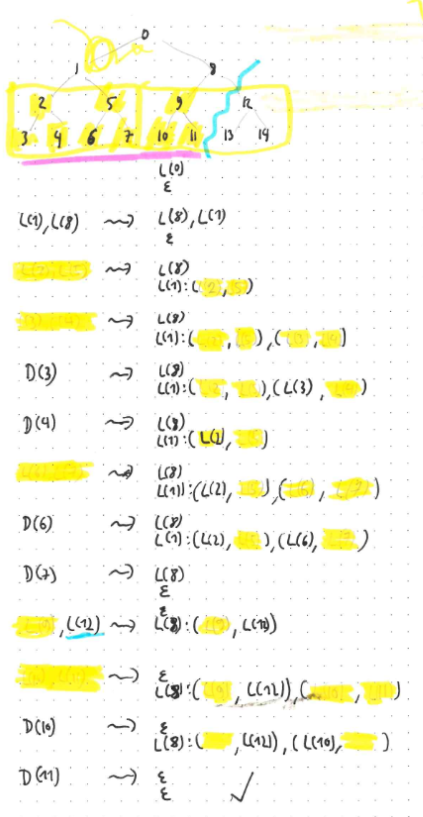

Let us start with an example of left-label omission (note that the verification process is not complete; also note that I write a lower-case epsilon to denote the empty stack):

The labels of yellow vertices are omitted from the stream, because they are omittable left labels.

The verification state now consists of the usual verification stack (initialised to containing a single label, namely the root label, shown with an orange underline), and an additional reconstruction stack (initialised to the empty stack, shown with a purple underline). While the reconstruction step is non-empty, you also store the currently reconstructed label (shown with a green underline). Here is how these work:

When receiving data with no omitted child label, everything works as before. When receiving data with an omitted left label, however, you set the currently reconstructed label to the previous top-of-stack of the verification stack. In the example, the initial state has the root label as the sole contents of the verification stack. After reading the first two labels (one of which is omitted, so you end up reading actual bytes for only a single label), the currently reconstructed label becomes the root label. Additionally, you do not push the omitted label onto the verification stack (how would you do that in the first place, it has been omitted so you do not know it). And finally, you push onto the reconstruction stack the information that a left label is missing, together with the corresponding right label.

In the next row of the example, we again receive data where one label has been omitted, so we do the same as before: we push the available right label onto the verification stack, and we push onto the reconstruction stack the information that another left label is missing and the corresponding right label.

In the next row of the example, we finally receive data with no label omissions. We use this data to pop from the reconstruction stack: from the received labels of vertices three and four, we reconstruct the label of vertex two. Popping from the reconstruction stack then tells us that we need to combine that reconstructed label with that of vertex five (the label of vertex five was stored on the reconstruction stack explicitly, so we can simply use it). Popping form the reconstruction stack again tells us to combine the result (which is the label of vertex 1) needs to be combined with that of vertex eight (again, handily part of the just-popped data). Popping again notifies us that the stack is empty. We still combine the labels to reconstruct a new label. Then we check whether this final reconstructed label is equal to the currently reconstructed label. If it is, then we have successfully verified all the data received so far. If it is not, we were fed garbage and we reject the data stream.

To make it absolutely clear: verification works whether you understand what is going on or you don't, all you have to do is follow the rules. The drawings show a lot of context that isn't even explicitly stored in the implementation: whenever the drawing says L(7), the computer only stores the bytes making up some label. It never explicitly stores that this label is that of vertex seven. Correct stack management ensures that the right labels are compared against the right reconstructions automoatically. These numbers help to understand what is going on, but computers thankfully do not require understanding.

This example has shown only left-label omission. The next and final example shows more flexible label omissions: both labels being omitted, or even only a right label being omitted (which can happen, because the rules for slice streams ensure that certain labels are present even if k-grouping would usually cause omission).

As before, the pink underline denotes the requested slice.

In the second step, we read no data at all, because both labels are omitted. Hence, we push onto the reconstruction stack the information that both a left and a right label need to be reconstructed (and while the drawing lightly says which to which vertices these labels correspond, that information need not actually be stored on the stack). Same for the third step.

In the next step, we receive the chunk data for vertex three (i.e., chunk zero). This allows us to reconstruct a label. We pop from the reconstruction stack, but with only a single avaiable label, we cannot reconstructing things. So we simply fill in the label we just reconstructed as the left label, and re-push this incomplete verification step onto the reconstruction stack.

Then, after receiving the chunk data for vertex four, we can reconstruct the label of vertex four. We pop fromt he reconstruction stack, and receive a partial reconstruction step with only a single label missing. So we combine the available label with the label we just reconstructed (the latter in the right position, because the information we popped from the reconstruction stack told us that a right label was missing), and thus reconstruct the label for vertex two. We pop from the reconstruction stack again, see that both labels are missing again, so we push onto the reconstruction stack the newly reconstructed label, plus the information that the right label is missing.

And in this manner, verification proceeds. Whenever you get data with omissions, you simply push to the reconstruction stack. Whenever you get data without omissions, you reconstruct a label, and then keep popping from the reconstruction stack to reconstruct as many more labels as possible. Either this stops at some point because you pop a “both-labels-are-missing” marker, in which case you replace it with a “only-the-right-label-is-still-missing” marker by filling in the final reconstructed label. Or this process stops because you empty the reconstruction stack, in which case you check for equality against the currently reconstructed label.

Note that I glossed over any correctness arguments. In particular, this algorithm would not be correct if label omissions could follow arbitrary patterns. But it does work for arbitrary left-label omissions and for omitting-everything-except-for-slice-boundaries-within-the-k-lowest-layer omissions. Yay. (Proof of yay is left as an exercise to the reader).